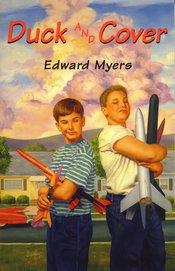

Duck and Cover by Edward Myers

That autumn America faced a harrowing crisis. Never before had the nation been so vulnerable to attack. An unexpected threat suddenly compromised the safety of all U.S. citizens, and everyone in the country waited anxiously to see if their inexperienced president could guide them to safety—or if danger would deteriorate into unimaginable catastrophe. The year wasn't 2001, but 1962. The danger wasn't terrorist attacks, but nuclear missiles in Cuba. If the U.S.-Soviet confrontation had degenerated into a shooting war, at least 100 million Americans and as many Soviet citizens would have died. In my forthcoming novel Duck 'n' Cover, Andy MacLean, a sixth grader in Denver, Colorado, doesn't fully understand what's happening around him. All he knows is that a terrible situation is taking shape. If the Americans and the Soviets end up fighting World War Three, the conflict will be the end of civilization. Like everyone else, Andy watches and waits, holding his breath, dreading the worst. But to complicate matters, he faces another crisis, a crisis that's taking shape right in his own schoolyard. Jim Smith, a boy Andy has known for years, suddenly turns against him. Far worse than an ordinary bully, Jim makes life miserable in every possible way—spreading rumors, distorting Andy's comments, turning friends against him, and threatening physical violence. Soon Andy finds himself in a conflict that seems as dangerous as the international tensions developing so far away. Andy can't help but wonder how he'll survive both of these crises: the big conflict out there in the world, and the smaller private conflict right in his own neighborhood.

- ISBN: 0-9674477-8-X

- Price: $11.95 (paper)

Read an Excerpt

1

That spring, when Andy MacLane was eleven, the whole world seemed to be turning into missiles. Play Land, the local toy store, filled its front window with toy missiles—rockets, bombs, and spaceships. The housewares department at Sears displayed a toaster shaped like a squat little missile. Woolworth’s sold a flashlight that resembled a silvery missile. There was a restaurant in town called the Atomic Diner that pointed skyward from the ground like a huge missile's metal nose cone. At Elitch's, the local amusement park, Andy rode on some missile-shaped rides: the H-bomb, the Rocket, and the Nuke. And the cars he saw—Chevies, Buicks, Chryslers, Fords, and especially Cadillacs—all had fins as big and pointy as the ones on the missiles in a Buck Rogers sci-fi movie. No matter where he looked, Andy saw missiles.

The year was 1962. That was the same year that John Glenn, the first American astronaut to orbit the earth, rode a Mercury-Atlas missile into space, and some Soviet cosmonauts went up, too, so there were real missiles whizzing through the air. Others hid in silos deep underground: Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, or ICBMs. Even kids like Andy knew about those, and worried about them. America's were the good ones—Minuteman, Titan, Jupiter, and Polaris—big missiles tipped with nuclear warheads aimed at the Soviet Union. The Soviet missiles were the bad ones (whatever they were called) loaded with huge H-bombs and aimed at the United States. No one he knew believed those ICBMs would ever really fly. The Americans and the Soviets wouldn't be so dumb that they'd start a war. A nuclear war. World War Three. Would they? That would be the end of civilization, maybe the end of the world. Andy felt sure those missiles would stay where they belonged, down inside their launch silos in Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and Siberia.

Yet he worried about them anyway. He couldn't help it—not with all those duck and cover drills to remind him.

The drills started in January, with Mr. Williams in charge. Mr. Williams was one of only two male teachers at John J. Cory Elementary School, in Denver, Colorado. He taught gym, mostly, and for some reason he was in charge of supervising the drills. Maybe that was because no one ever argued with Mr. Williams. All the kids loved him: the boys because he was big and strong and knew everything about sports; the girls because he was so handsome and polite. Andy liked Mr. Williams because he didn't make fun of him for being bad at sports, and because he also taught science class, which Andy loved. Mr. Williams was weird in one way, though: he referred to all the kids as Mister or Miss. "Miss Santucci, would you care to demonstrate a forward roll?" he'd ask in gym class. Or, in science class, he'd tell Andy, "Mr. MacLane, please explain the basic principles of jet propulsion." Some of the boys thought that a man as big and strong as Mr. Williams was weird to be so polite, but everyone regarded Mr. Williams as the right person to supervise duck and cover.

The fifth graders would be right in the middle of a spelling test, a civics lesson, or an art project, when suddenly Mr. Williams would shove open the door, rush into the classroom, and shout, "Duck and cover!" Most of the kids would then immediately crouch under their desks and assume the position they'd been taught: kneeling, hunching low, with one arm across the back of the head and the other pulled across the eyes. A few kids, mostly boys, would just sit there, staring at Mr. Williams. "I said, Duck and cover!" Mr. Williams would bellow. Then the stragglers would crawl beneath their desks and assume The Position. A minute or two later, while everyone grunted and giggled, Mr. Williams would say, "All clear."

What followed was The Duck and Cover Speech. "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't believe you understand the seriousness of what we're doing," Mr. Williams would say as the fifth graders forced themselves up and sat in their seats again. "No, I don't see any signs of that. Mr. Wagner, do you think I'm doing this for my health? Mr. Jenner? Mr. Peck? When I shouted Duck and cover, you just sat there and stared at me. What would have happened if this hadn't been a drill? What would have happened if a Soviet missile had detonated at just that moment over downtown Denver? Hmm? Tell me that."

The speech always went on for a long time. Then Mr. Williams would thank Mrs. Johnson, who was Andy's teacher that year and whose hairdo looked as if she'd jammed a beehive onto her head, and Mr. Williams would leave. Everyone in Mrs. Johnson's classroom would listen closely for Mr. Williams' voice as he entered Mrs. Murdo's room next door: "Duck and cover!"

That was just one kind of drill. Another kind started with bells: short, loud rings that went on for a long time. The children were supposed to hide under their desks for those drills, too, just like when Mr. Williams burst in and shouted. Still another kind began with long rings, which meant that the students in each class filed out of their classroom, joined other lines of kids, and proceeded in an orderly manner through the halls, down the staircases, and into the basement of Cory School, where, shuffling and bumping into one another, they would crouch head-first against the cool, ceramic-tiled walls of a windowless hallway and wait.

One April afternoon, Andy and all the other kids heard the long bells, filed out of their classrooms, descended the staircase into the school's basement, and assumed The Position. Five minutes passed. Ten. Fifteen, maybe more. Everyone got restless, muttering and groaning, and a few even called out: "Miss Brown, can I go to the bathroom?" or "When's the all-clear?" or "Get your elbow out of my face!" The Position grew more and more uncomfortable as the drill went on and on, but Andy felt too scared to move or talk or do anything but wait. This drill was the longest ever. What if this isn't a drill? he suddenly wondered. What if this is the real thing? Maybe the teachers said it was a drill when it really wasn't. Maybe they were trying to keep the children calm by tellingeveryone it was a drill. Maybe Russian missiles were heading over the North Pole and streaking toward John J. Cory Elementary School in Denver, Colorado, even as all the kids in the basement tried to keep still and maintain The Position.

Andy tried to figure out what was happening. He didn't really understand why anyone needed all these duck and cover drills in the first place. It was something about the Soviet Union and Nikita Khrushchev and Communism and Soviet H-bombs, of course—that much he knew. The Russians hated the Americans and the Americans hated the Russians. Blah blah blah. But it made no sense. All Andy knew was that he hated duck and cover drills and he wanted to go home. If this was just a drill, he wanted to go home because he was bored. If it wasn't a drill, Andy wanted to go home because he wanted to be with Mom and Dad, who would protect him better than Mrs. Johnson, Mr. Williams, and all the other teachers at Cory School. Andy wanted to be with his parents and wanted them to say that everyone would be fine. He didn't want to crouch in the school basement with a bunch of kids.

Uncovering his eyes and craning his neck, he could see some of the children around him. Most of them were maintaining The Position. A few—Randy Wagner, Bruce Cray, and Jim Peck—were goofing off. Whispering. Jabbing each other. Giggling and belching. Some were trying to look around, just like Andy. He didn't want to get in trouble, but the long wait for the all-clear signal left him so concerned that he needed to check out the situation. He felt too scared simply to stay crouched in The Position for so long without moving. He needed to know what was happening.

Some of the teachers stood nearby in the basement hallway. Andy couldn't see more than two of them—Miss Brown, whose beaky nose and beady eyes made her resemble some kind of hawk or falcon, and Mr. Shafer, who always wore a neatly pressed white shirt and a dark blue tie only one inch wide—but he could hear others nearby. Mr. Williams, whose low voice was easy to detect. Mrs. Johnson, whose voice Andy recognized because he heard it so often. Others too. Talking softly. Even chuckling now and then. They didn't seem upset, anxious, or afraid. They just stood there, watching and waiting, now and then scolding some of the children: "Randy, get your head down. Brent? Barry?" If Soviet missiles were really streaking toward Denver, Colorado, the teachers wouldn't be standing around, Andy told himself. They'd be assuming The Position, too. He felt less and less worried as the long minutes passed.

But what if they're faking it? he asked himself. Maybe the teachers are just trying to seem relaxed. They know everyone is doomed. Instead of showing their alarm, though, they're chatting and chuckling, standing around with their arms crossed, just to keep the kids under control. They know this is the real thing. In a few minutes, a Russian H-bomb will detonate and everyone will die.

A great wave of fear and sadness washed over him. Andy couldn't believe he'd die so young. Eleven years old! He'd never have a chance to grow up. He'd never learn to drive or go to college. He'd never leave Denver, Colorado, and go explore the world. He'd never become a brilliant scientist. He'd never win the Nobel Prize and return from Sweden after the ceremony to find himself famous throughout America. The cruelty and unfairness of the situation brought tears to his eyes and a sour taste to his throat.

He looked up again. Left, right. Somehow he'd ended up surrounded by girls: Linda Brown on his left, Lisa Stanley on his right. Linda was a tomboy but had the smallest teeth of any kid his age—perfectly white teeth that resembled the tiny, powdery mints that Andy always took from a bowl near the cash register whenever his family went out for dinner at the Pagoda Chinese Restaurant. Lisa Stanley was the best-behaved kid in the fifth grade: she sat in class with her fingers interlaced and both hands resting on her desk, she never moved or spoke till someone told her what to do, and she got straight A's year after year. Andy was stuck between these girls! No doubt he'd catch heck from the boys for this bad luck later, at recess. Andy set to work thinking up insults to say about Linda Brown and Lisa Stanley so the boys wouldn't think he had enjoyed getting stuck between them.

Then, peeking under his left armpit, Andy looked across the hallway. Girls everywhere. He recognized Janice Milton, Barbie Sanders, and Susie Santucci. Janice and Barbie both had straight yellowish hair and pale skin. Andy’s shoes, pointed toe-backward, came within a foot of touching Susie's. Susie Santucci stayed tan all year round and had long, curly brown hair that bounced and quivered when she walked. Now Andy sized up these girls through the window formed by his chest, upper arm, and forearm. They were tucked into compact mounds: backs curved, rumps protruding slightly, dresses draped neatly around their legs, white socks and brown-and-tan saddle shoes pressed hard against the floor. Andy noticed that Susie's dress had gotten flipped up a bit, revealing the backs of her thighs. This sight filled Andy with a strange, tingling discomfort.

"Mr. MacLane," said Mr. Williams. "Head down, proper position."

Which left him in the dark, the crook of his left arm pressed hard against his face, with nothing to see and nothing to do but wait for the all-clear signal, which would come in five, ten, fifteen minutes...

Still, Andy told himself, the situation could have been worse. Much worse. Andy could have ended up right next to Jim Smith.

Duck and Cover has been added to your shopping cart.